Signal Processing for Interactive Systems

Cumhur Erkut (cer@create.aau.dk)

Aalborg University Copenhagen.

Last edited: 2026-02-26

The discrete-time Fourier transform¶

In this part, you will learn

why it is important to look at signals in the frequency domain

what the DTFT is

how you can visualise noise removal in the frequency domain

🔈 Understanding the DFT and the FFT (20 minutes): MATLAB Path is prefered. Content on MATLAB Online: You will be prompted to log in or create a MathWorks account. The project will be loaded, and you will see an app with several navigation options to get you started.

Example: analysing a trumpet signal Suppose that we record a trumpet signal for .

try:

import google.colab

IN_COLAB = True

!mkdir -p data

!wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/SMC-AAU-CPH/med4-ap-jupyter/main/lecture7_Fourer_Transfom/data/trumpet.wav -P data

!wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/SMC-AAU-CPH/med4-ap-jupyter/main/lecture7_Fourer_Transfom/data/trumpetFull.wav -P data

except:

IN_COLAB = False

# %matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import scipy.io.wavfile as wave

import IPython.display as ipd

import librosa

# If needed you can load the trumpet full audio file, and crop the beginning for a single note as trumpet.wav

# audio_data, sampling_rate = librosa.load(librosa.ex('trumpet'))# load a trumpet signal

samplingFreq, cleanTrumpetSignal = wave.read('data/trumpet.wav')

cleanTrumpetSignal = cleanTrumpetSignal/2**15 # normalise

ipd.Audio(cleanTrumpetSignal, rate=samplingFreq)nData = np.size(cleanTrumpetSignal)

timeVector = np.arange(nData)/samplingFreq # seconds

plt.figure(figsize=(14,6))

plt.plot(timeVector,cleanTrumpetSignal,linewidth=2)

plt.xlim((timeVector[0],timeVector[-1]))

plt.xlabel('time [s]'), plt.ylabel('$s_n$');

The discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT)¶

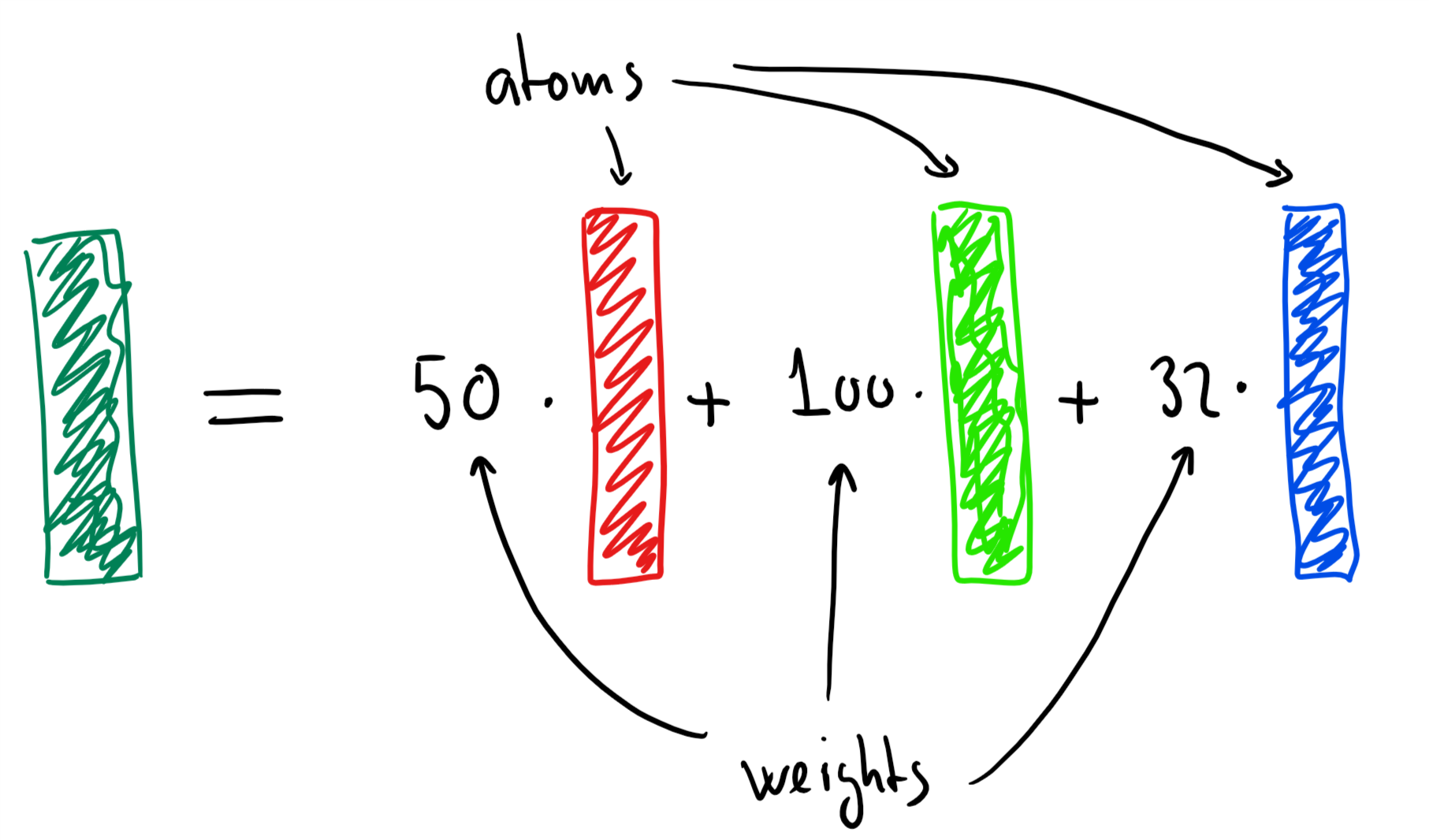

Any colour can be written as a weighted combination of three atoms (red, green and blue colours).

A signal (such as the trumpet signal) can be written as a weighted combination of phasors, i.e.,

This is called the inverse discrete-time Fourier transform (inverse DTFT).

We can find the weights by correlating our signal to the phasor , i.e.,

This is called discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT).

Note that

the DTFT is mostly of theoretical interest since we will never encounter infinitely long signals in practice

the practical version of the DTFT is called the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) (more on this later)

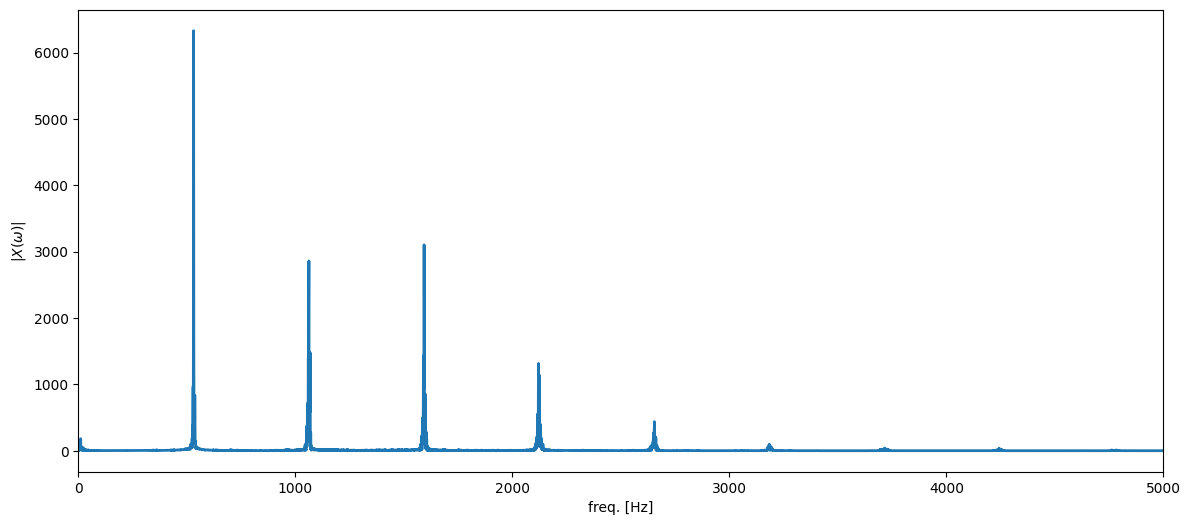

Example: analysing a trumpet signal¶

Let us now (pretend that we can actually) compute the DTFT of the trumpet signal, i.e.,

with being the trumpet signal. (In practice, we are computing the DFT, but we will return to that later).

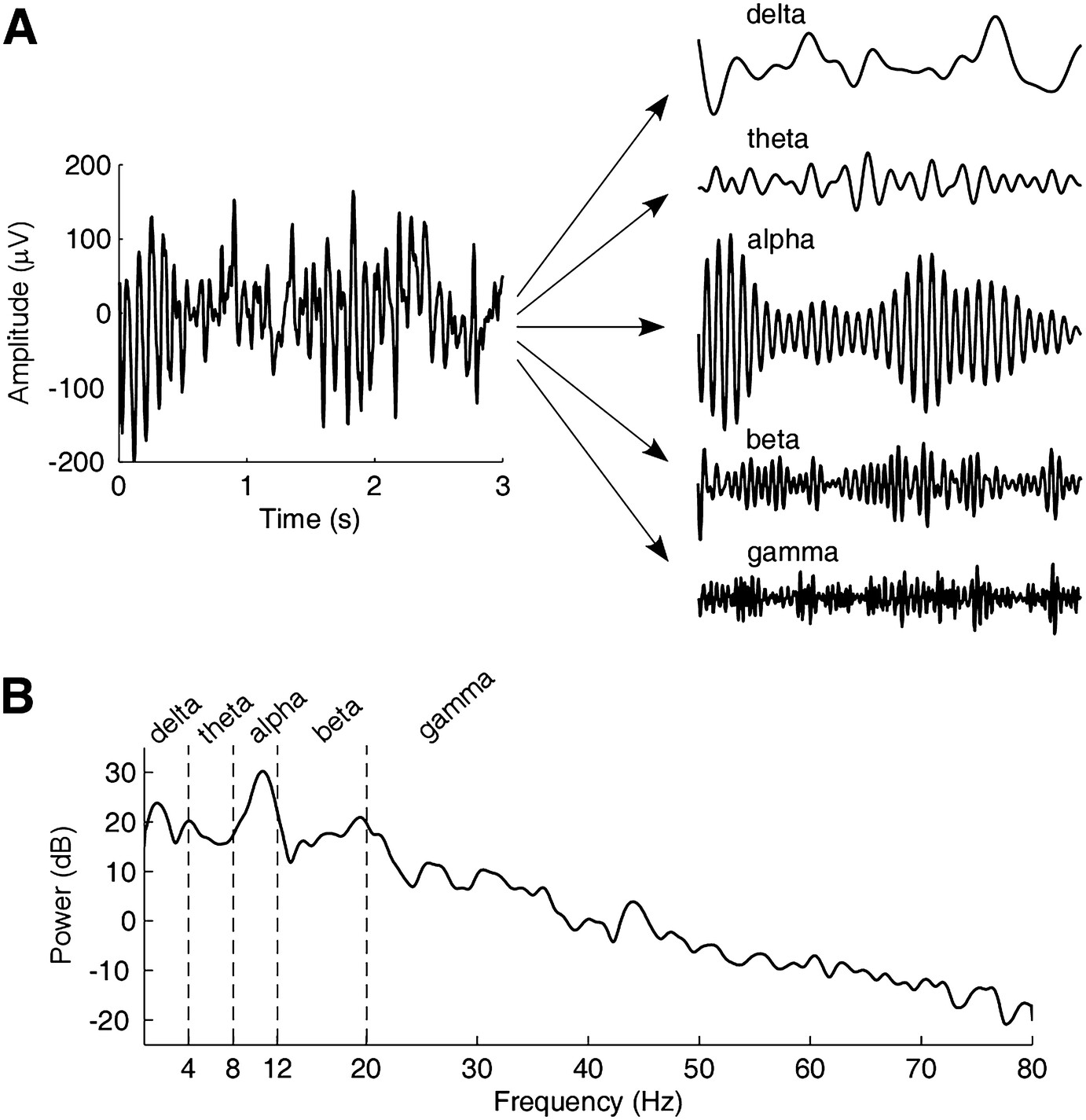

Example: An EEG Signal (eyes closed)¶

Time-domain representation and frequency-domain representation (the spectrum) of anEEG signal with eyes closed. (a) The EEG signal is recorded at Oz and has a duration of 3 s and asampling rate of 160 Hz. By using bandpass filtering with difference cutoff frequencies, the signalcan be decomposed into five rhythms. (b) The spectrum of the EEG signal. After Zhang, Zhiguo. 2019. “Spectral and Time-Frequency Analysis,” in 89–116. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-9113-2_6. In “EEG Signal Processing and Feature Extraction”, edited by Li Hu and Zhiguo Zhang, 2019.

freqVector = np.arange(nData)*samplingFreq/nData # Hz

# we compute the DFT using an FFT algorithm

freqResponseClean = np.fft.fft(cleanTrumpetSignal)

ampSpectrumClean = np.abs(freqResponseClean)

plt.figure(figsize=(14,6))

plt.plot(freqVector,ampSpectrumClean,linewidth=2)

plt.xlim((0,5000)) # up to 5 KHz

plt.xlabel('freq. [Hz]'), plt.ylabel('$|X(\omega)|$');

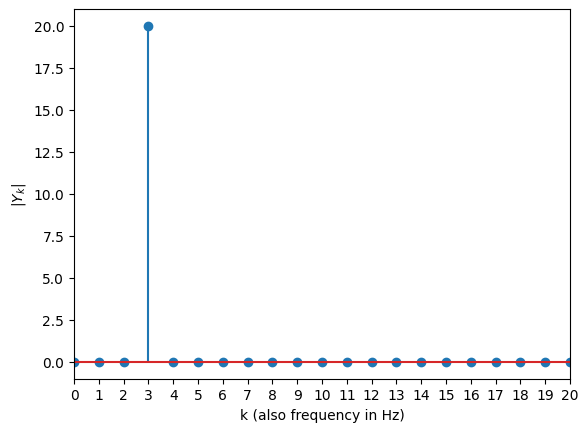

Sine Signal¶

fs = 40

T = 1/fs

N = 40

# create time index for 1 seconds of a signal

t = np.arange(N)*T

# assign 3 Hz as frequency. TODO make it changable with a slider

xn = np.sin(2*np.pi*3*t)

One-sided FFT¶

# One-sided FFT

Y = np.fft.fft(xn)

plt.figure

plt.stem(abs(Y))

# stem plot only up to half of Nyquist, make all integer ticks visible

plt.xticks(np.arange(0,N/2+1,1))

plt.xlim((0,N/2))

plt.xlabel('k (also frequency in Hz)'), plt.ylabel('$|Y_k|$')

plt.show()

# Note: we don't normalize to match the video, if we'd divide Y_3 to N/2 = 20, we would.

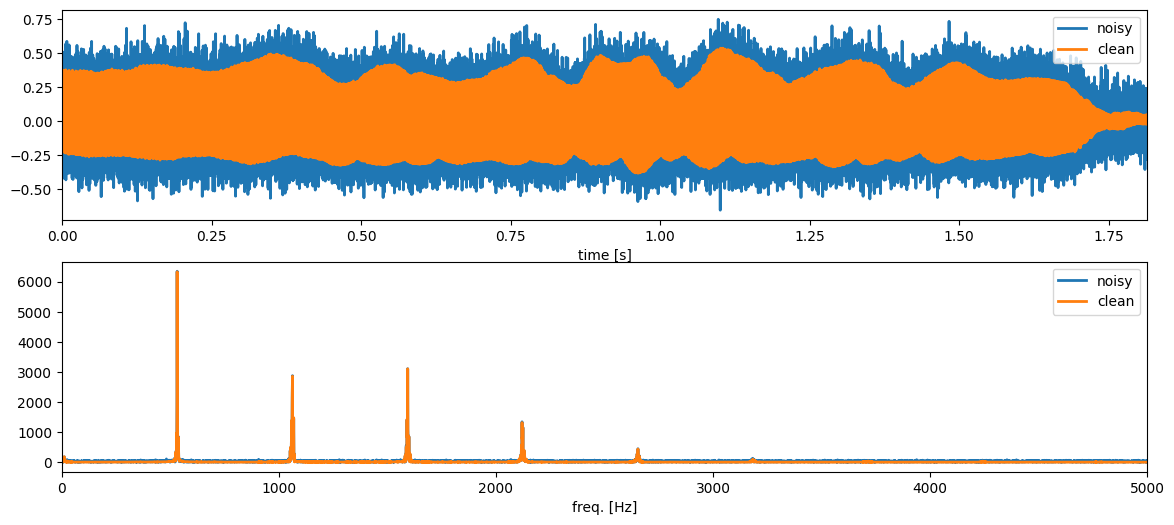

Example: a noisy trumpet signal (Anatomy of a classical-frequency domain DSP problem)¶

Let us now assume that we record a noisy trumpet signal. We can write this as

where

is the noisy trumpet signal

is the clean (i.e., noise-free) trumpet signal

is the noise

# add noise to the trumpet signal

noise = np.sqrt(0.01)*np.random.randn(nData) # generate so-called white Gaussian noise (WGN)

noisyTrumpetSignal = cleanTrumpetSignal + noise

freqResponseNoisy = np.fft.fft(noisyTrumpetSignal)

ampSpectrumNoisy = np.abs(freqResponseNoisy)

ipd.Audio(noisyTrumpetSignal, rate=samplingFreq)In the frequency-domain, the noisy trumpet signal can be written as

where

is the DTFT of the noisy trumpet signal

is the DTFT of the clean trumpet signal

is the DTFT of the noise

We see that the Fourier transform is additive. Thus, if we sum two signals in the time domain, we also sum them in the frequency domain. This is illustrated for the two signals and in the figure below.

plt.figure(figsize=(14,6))

plt.subplot(2,1,1)

plt.plot(timeVector,noisyTrumpetSignal,linewidth=2, label='noisy')

plt.plot(timeVector,cleanTrumpetSignal,linewidth=2, label='clean')

plt.xlim((timeVector[0],timeVector[-1])), plt.xlabel('time [s]'), plt.legend()

plt.subplot(2,1,2)

plt.plot(freqVector,ampSpectrumNoisy,linewidth=2, label='noisy')

plt.plot(freqVector,ampSpectrumClean,linewidth=2, label='clean')

plt.xlim((0,5000)), plt.xlabel('freq. [Hz]'), plt.legend();

A typical SPIS Problem and towards a solution: removing noise from a trumpet signal¶

Note that

the trumpet signal only has almost all of its energy concentrated in a few frequencies at (approximately) 530 Hz, 1060 Hz, 1590 Hz, 2120 Hz, 2650 Hz, etc. (These values have been estimated using a pitch estimator which we are going to discuss in lecture 12)

the noise is spread across all frequencies

we can remove a lot of noise by processing the bands above a filter which will only allow the ‘trumpet frequencies’ to pass through.

Summary¶

The discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT) of a signal is given by

You can think of the DTFT as a correlation between a signal and a phasor of frequency .

The inverse DTFT of a frequency response is given by

You can think of the inverse DTFT as writing the signal as a weighted sum of phasors.

Signals are often much easier to process and analyse in the frequency domain.

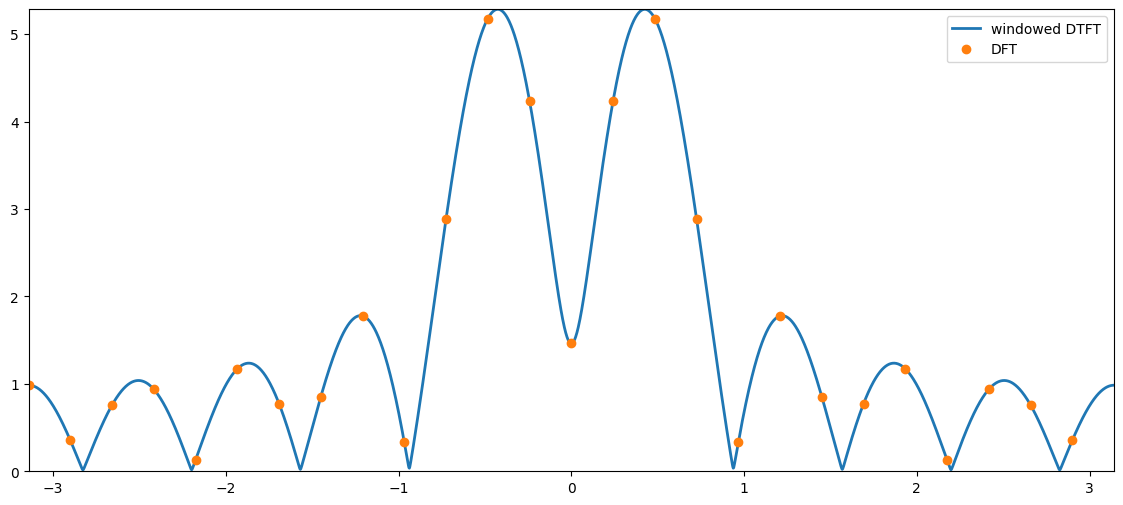

The discrete Fourier transform¶

how the DFT is defined

how the DFT is related to the DTFT

The discrete Fourier transform¶

The discrete Fourier transform (DFT) is a sampled version of the windowed DTFT, i.e.,

where the digital frequencies are evaluated on a -point grid given by

with .

💡Note that this can be interpreted as applying a rectangular window, a .

Often, the expression for is inserted directly into the DFT definition and we obtain

# %matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

windowLength = 10

signalFreq = 0.3 # radians/sample

signal = np.cos(signalFreq*np.arange(windowLength))

nFreqsDtft = 2500

freqGridDtft = 2*np.pi*np.arange(nFreqsDtft)/nFreqsDtft-np.pi

windowedDtftSignal = np.fft.fftshift(np.fft.fft(signal,nFreqsDtft))

nFreqsDft = 26

freqGridDft = 2*np.pi*np.arange(nFreqsDft)/nFreqsDft-np.pi

dftSignal = np.fft.fftshift(np.fft.fft(signal,nFreqsDft))plt.figure(figsize=(14,6))

plt.plot(freqGridDtft,np.abs(windowedDtftSignal), linewidth=2, label='windowed DTFT');

plt.plot(freqGridDft,np.abs(dftSignal), 'o', linewidth=2, label='DFT')

plt.xlim((freqGridDtft[0],freqGridDtft[-1])), plt.ylim((0,np.max(np.abs(windowedDtftSignal)))),plt.legend();

The fast Fourier transform¶

The fast Fourier transform (FFT) computes the DFT, but is a computationally efficient way.

Note that

computing the DFT directly from its definition costs in the order of floating point (flops) operations (we write this as ).

computing the DFT using an FFT algorithm reduces the cost to just flops

most FFT algorithms are working most efficiently when is an integer

most FFT algorithms are slow (relatively speaking) if is prime or has large prime factors (i.e., if you factorise into a product of prime numbers and any of these are large, then most FFT algorithms will be slow)

entire books have been written on FFT algorithms, but the most important thing to remember is that they are all just different ways of compute the DFT as fast as possible!