Central question

How are analog signals turned into digital representation (i.e., data) on a computer?

How can we analyse these digital signals (i.e. extract information from them)?

How can we modify these signals? How can we convert them back to analog signals?

Full Jupyter: Sampling and reconstruction¶

In the next 20 minutes, you will learn

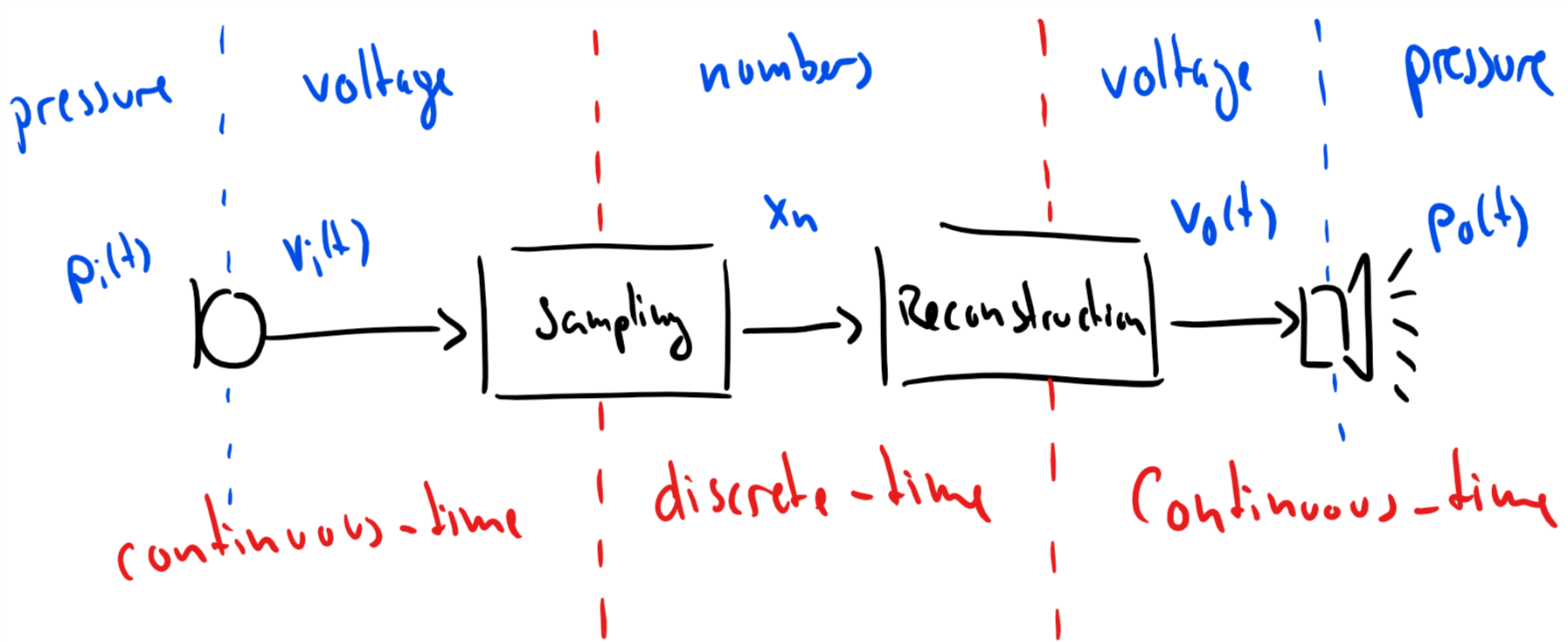

What a continuous-time signal is.

What a discrete-time signal is.

How you turn a continuous-time signal into a discrete-time signal (i.e., sampling).

How you turn a discrete-time signal into a continuous-time signal (i.e., reconstruction).

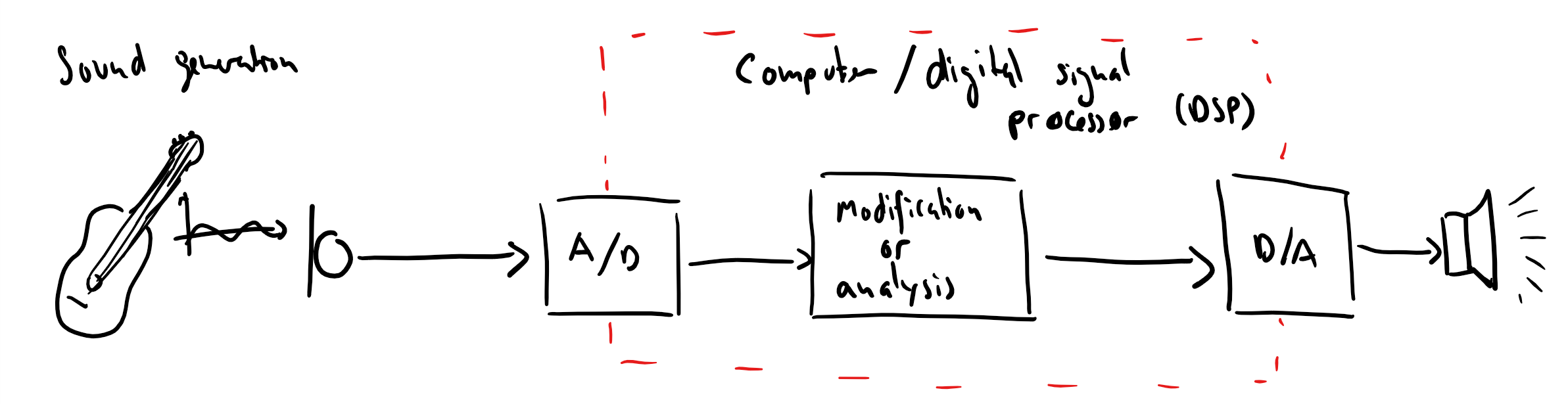

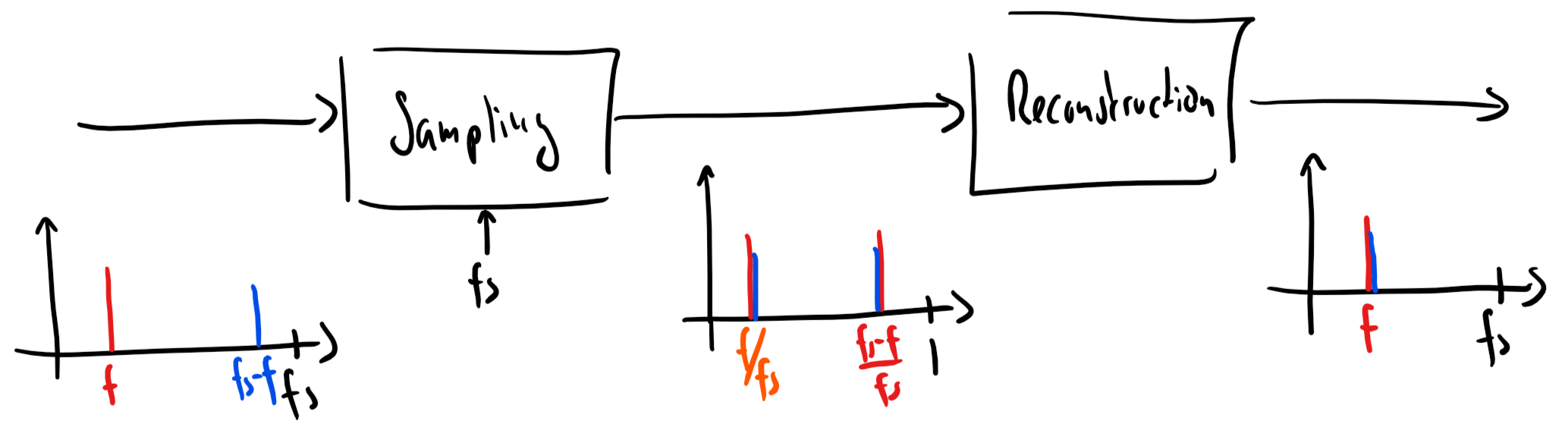

In the figure below, the following is happening:

An audio signal is propagating through the air as pressure variations.

The microphone picks up the pressure variations and turns them into voltage variations .

The voltage is converted into a series of numbers via sampling.

A voltage signal is reconstructed from the series of numbers .

A loudspeaker converts the voltage variations into pressure variations .

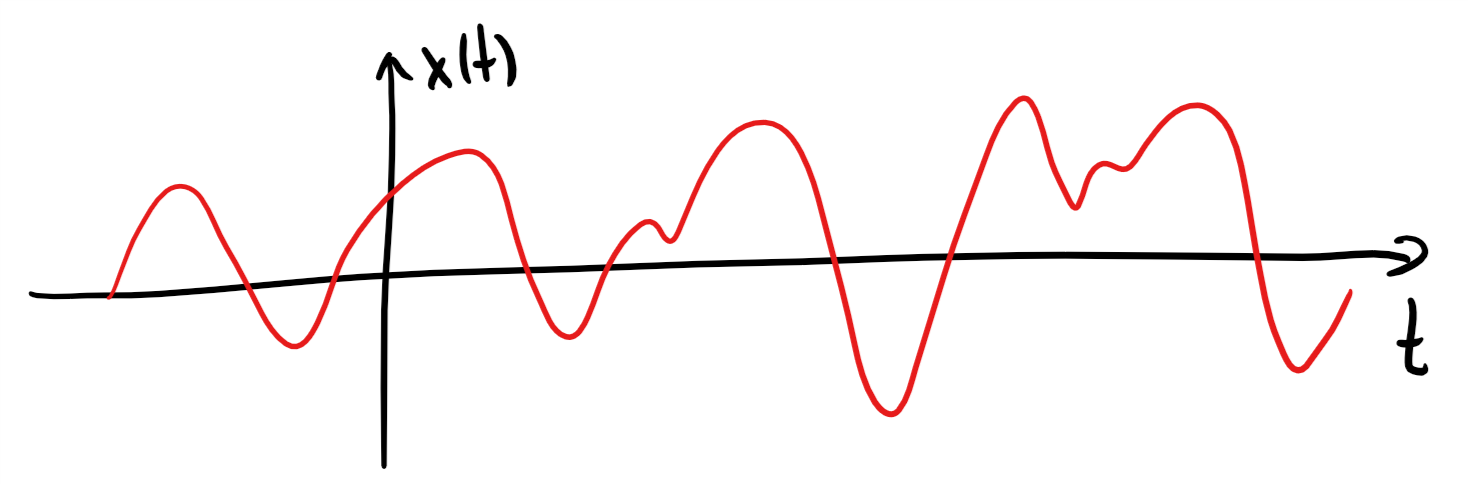

Continuous-time signal¶

A continuous-time signal is characterised by

time: the signal has a value for every possible time

amplitude: the signal value can take on any value from a continuum of numbers (such as the real numbers).

A continuous-time signal is often also referred to as an analog signal.

Informally: You draw a continuous-time signal without lifting your pen from the paper.

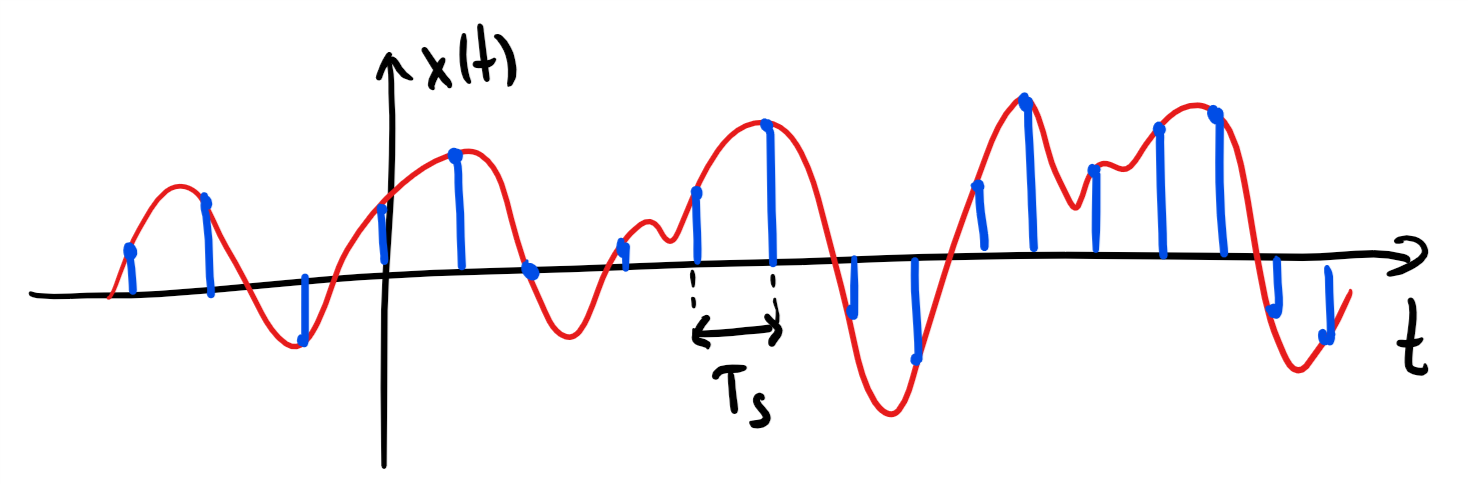

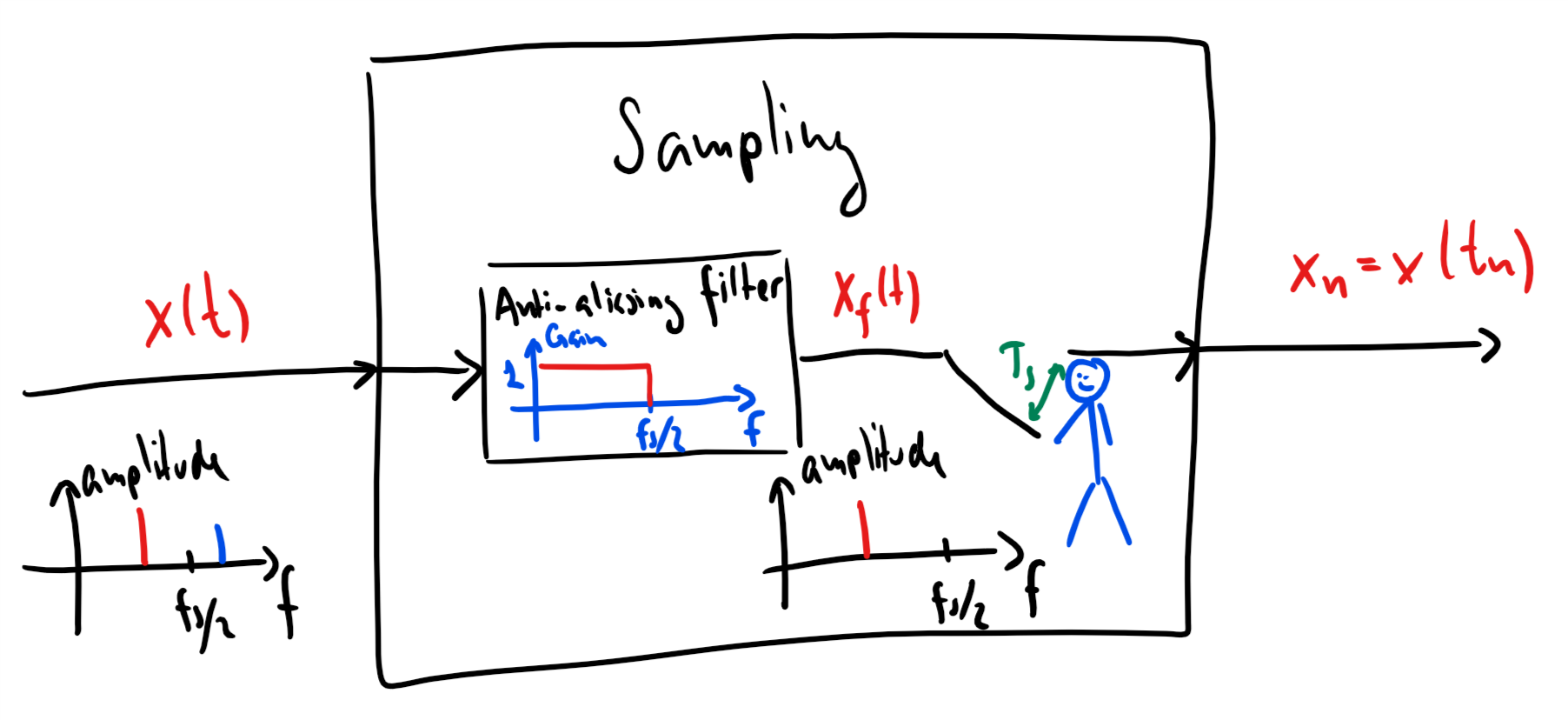

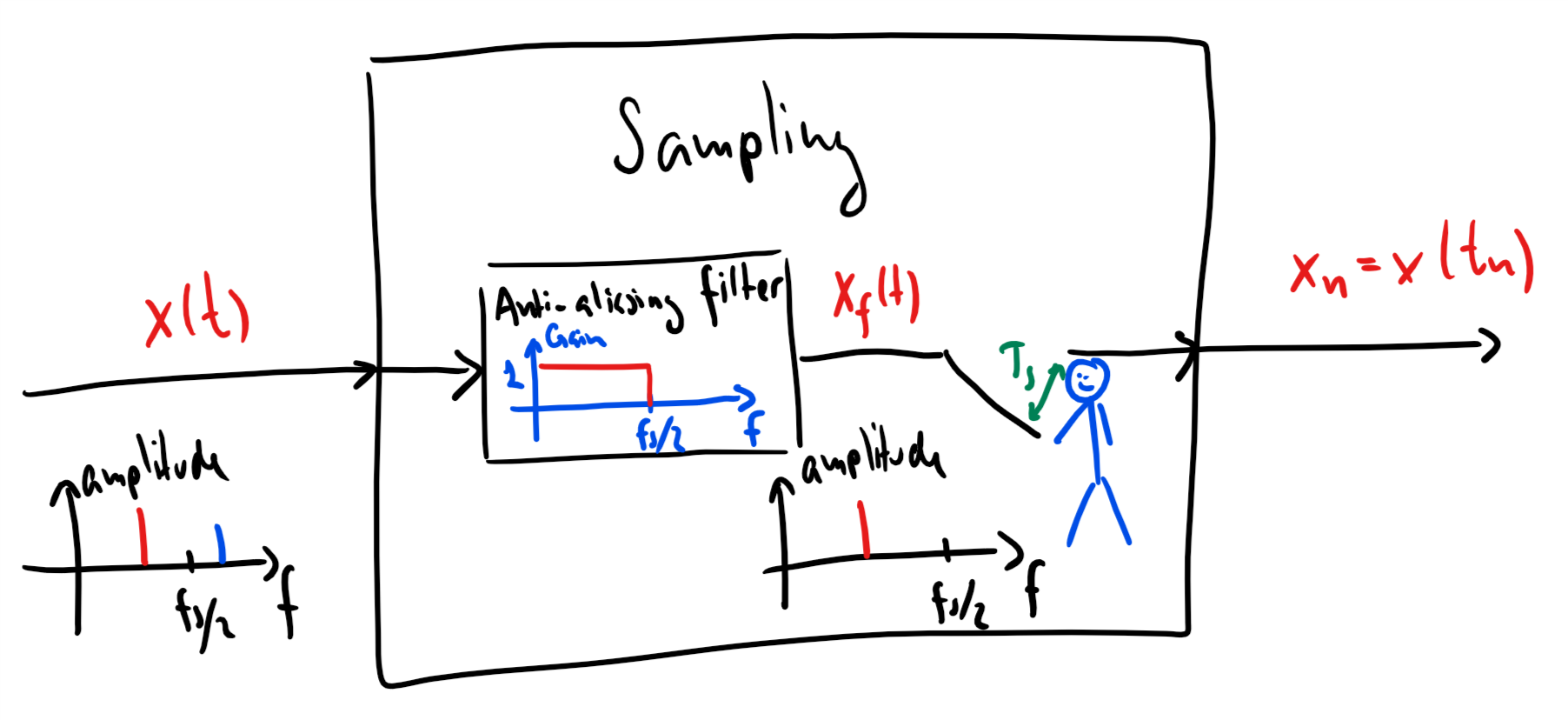

Sampling¶

Storing a continuous-time signal on a computer requires an infinite amount of memory!

Solution: We only measure the value of a continuous-time signal every seconds. This is called sampling.

A very important quantity is

where

is the sampling frequency (measured in Hz) and describes how many times per second the continuous-time signal is sampled

is the sampling time (measured in seconds).

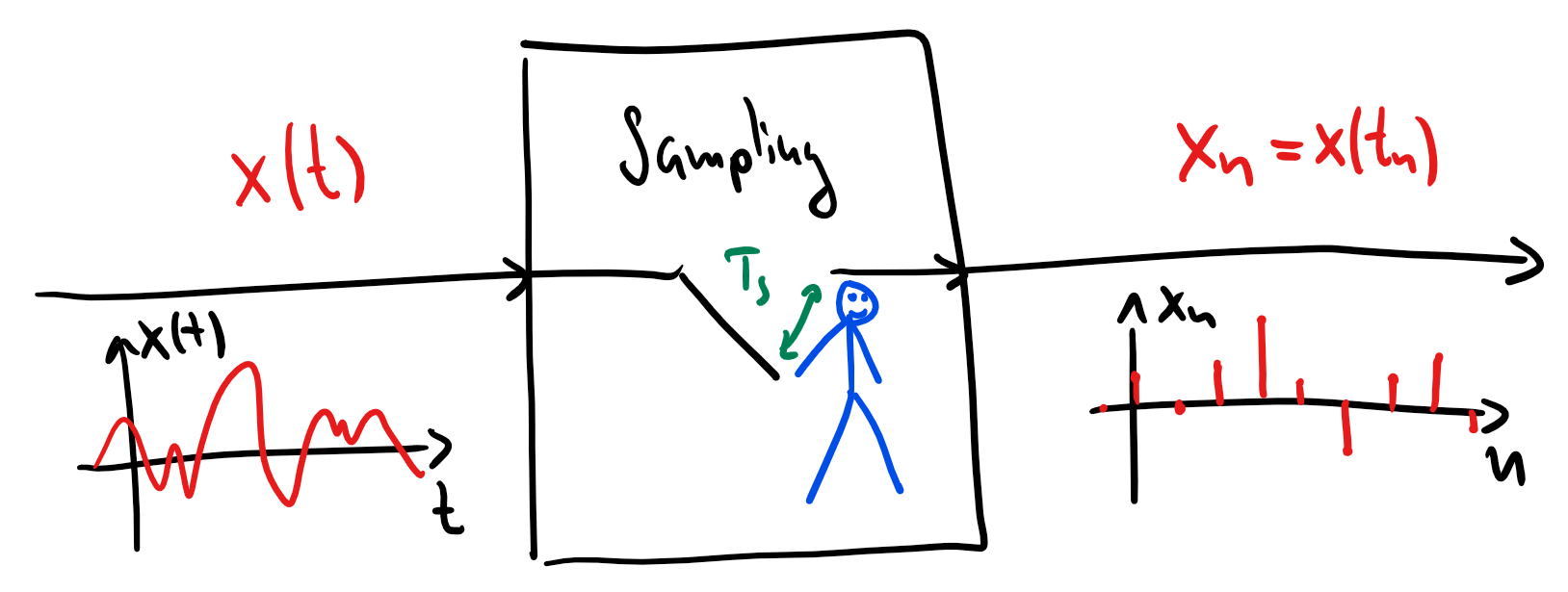

We can illustrate sampling by a person controlling a contact (see figure below):

When seconds has passed, the contact is pushed and released immidiately.

At that exact time instant, the value of the continuous-time signal is stored on the computer.

After another seconds, the contact is again pushed and released immidiately so that is now stored.

If we keep pushing/relasing the contact every seconds, we will after times store the signal value where

The scaler is often referred to as the sampling index.

Note that people often write as

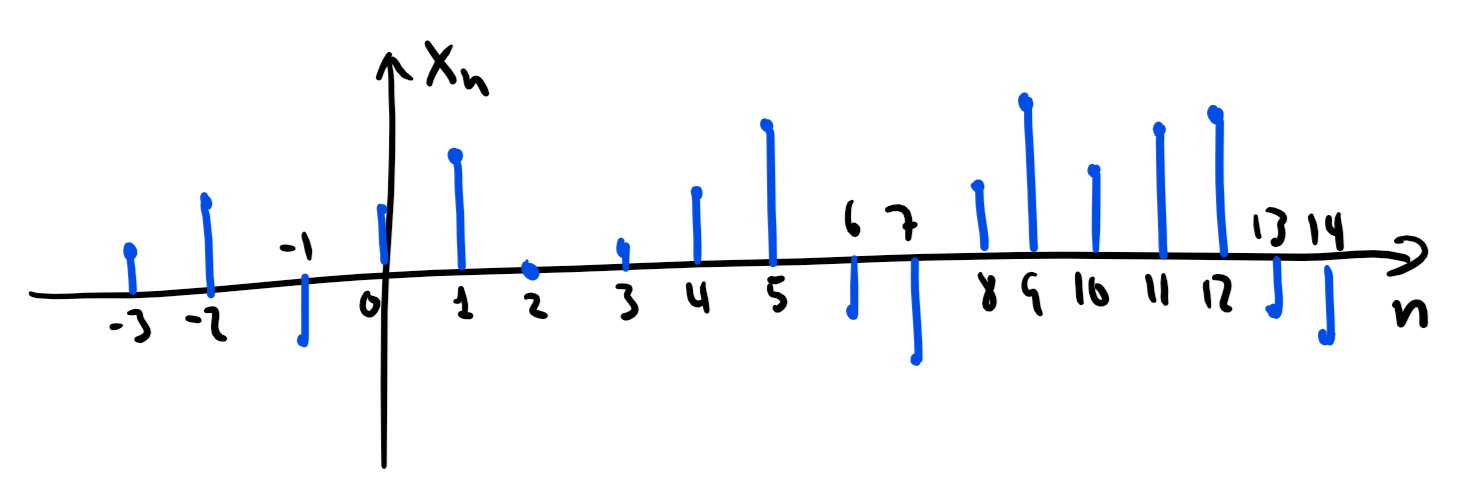

Discrete-time signal¶

A discrete-time signal is characterised by

time: the signal only has a value at certain times, i.e., for . Therefore, the -axis is often the sampling index instead of time.

amplitude: the signal value can take on any value from a continuum of numbers (such as the real numbers).

A discrete-time signal is sometimes also referred to as a digital signal (although we will use this term for something slightly different later).

Informally: A discrete-time signal is a series of time-ordered numbers.

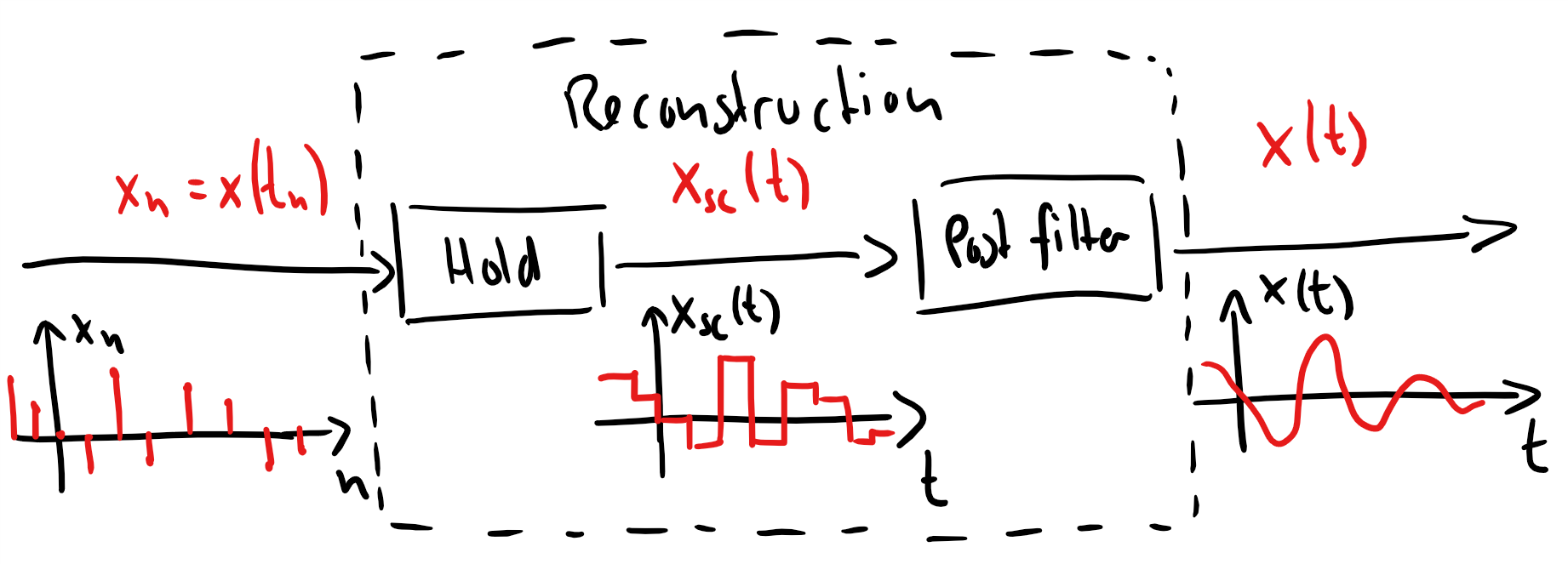

Reconstruction¶

If we want to play back a discrete-time signal on, e.g., a loudspeaker, we have to convert the discrete-time signal back into a continuous-time signal.

Converting a discrete-time signal into a continuous-time signal is called reconstruction.

Reconstruction is performed using two components:

hold circuit: holds a value for seconds. This will create a staircase signal.

post filter: smooth out the discountinuities in the staircase signal by using a low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of Hz.

Note that we will talk much more about filtering in the next lectures.

Summary¶

A continuous-time signal can be drawn without lifting the pen from the paper.

A discrete-time signal is a series of time-ordered numbers.

Sampling converts a into by measuring the value of at the times

where

is the sampling index

is the sampling time

is the sampling frequency

Reconstruction converts into by first creating a staircase signal from and then by filtering this staircase signal with a low-pass filter.

Aliasing¶

In the next 20 minutes, you will learn

How we write a discrete-time sinusoid.

What aliasing is.

How we can avoid aliasing by selecting the sampling frequency .

What an anti-aliasing filter is and why we need it.

Discrete-time sinusoid¶

As we have seen in the first two lectures, a continuous-time sinusoid can be written as

where

is an amplitude

is a frequency measured in rad/s

is the inial phase.

Let us now sample this signal with a sampling frequency of Hz. We then get the discrete-time sinusoid

where

is the digital frequency measured in radians/sample.

For a discrete-time signal, corresponds to the sampling frequency, and we will also write this frequency as .

What is Aliasing?¶

Aliasing comes from the word alias.

It refers to that a sinusoidal component of one frequency is ‘disguising’ itself as a sinusoidal component with another frequency.

As an example, let us try to sample these continuous-time sinusoids

using a sampling frequency of Hz.

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from ipywidgets import interact

def sinusoid(samplingIndices, digitalFreq):

'''Compute a cosine'''

return np.cos(2*np.pi*digitalFreq*samplingIndices)

def plot_aliasing(samplingFreq=100):

nData = 100

samplingTime = 1/samplingFreq # s

samplingIndices = np.arange(nData)

time = samplingIndices*samplingTime

freqA = 10 # Hz

freqB = samplingFreq - freqA # Hz

# plot the results

plt.figure(figsize=(10,6))

plt.plot(time, sinusoid(samplingIndices,freqA/samplingFreq), linewidth=2, marker='o', label=f"$x(t)$, f={freqA}Hz")

plt.plot(time, sinusoid(samplingIndices,freqB/samplingFreq), linewidth=2, marker='o', label=f"$y(t)$, f={freqB}Hz")

plt.legend()

plt.xlim((time[0],time[nData-1])), plt.ylim((-1.5,1.5))

plt.xlabel('time [s]'), plt.ylabel('Amplitude [.]')

plt.title(f'Sampling Frequency: {samplingFreq} Hz')

plt.show()

interact(plot_aliasing, samplingFreq=(50, 150, 1));Observation: Even though the continuous time signals and have different frequencies, the discrete-time signals and have the same digital frequency.

Some consequences:

Reconstructing a continuous-time signal from results in - not .

We say that has been aliased when we cannot recover it again after sampling it.

A discrete-time sinusoid of digital frequency , could be a sampled continuous-time sinusoid given by

for any integer .

Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem¶

To avoid aliasing, the maximum frequency in a continuous-time signal must satisfy that

where is the sampling frequency.

We can satisfy the sampling theorem in two ways:

Select the sampling frequency high enough

Pre-filter the continuous-time signal with a low-pass filter (a so-called anti-aliasing filter) with a cut-off frequency below .

Typical sampling frequencies used for recording audio¶

| Application | Sampling frequency |

|---|---|

| IMU | 200 Hz |

| XR controllers | 1000 Hz |

| Narrowband speech | 8000 Hz |

| Wideband speech, VoIP | 16000 Hz |

| CD Audio | 44100 Hz |

| Video recorders | 48000 Hz |

| DVD-audio and Blu-ray | 96000 and 192000 Hz |

| Sonar | 200000 Hz |

Anti-aliasing filter¶

Often, we do not know the highest frequency in our input signal.

Instead, we simply filter out all frequency content above to avoid aliasing.

This filter is called an anti-aliasing filter and is present in all practical sampling blocks.

Aliasing also occours in videos and images¶

Summary¶

A discrete-time sinusoid is written as

where and have the same meaning as for the continuous-time sinusoid and

is the digital frequency and measured in rad/sample

is the sampling frequency measured in Hz.

Aliasing refers to when the frequency of a sinusoid is lowered due to undersampling the signal.

To avoid aliasing, we must satisfy Nyquist’s sampling theorem stating that

where is the maximum frequency in the continuous-time input signal.

We can limit the maximum frequency of a continuous-time input signal by passing it through an anti-aliasing filter. This filter, which is a low-pass filter, ensures that aliasing does not occur.

Binary numbers¶

In the next 20 minutes, you will learn

What a binary number is

What a bit and a byte is

How you store data on, e.g., a computer or a CD

To get the following slightly geeky joke :)

There are 10 types of people in this world. Those who understand binary numbers and those who don’t!

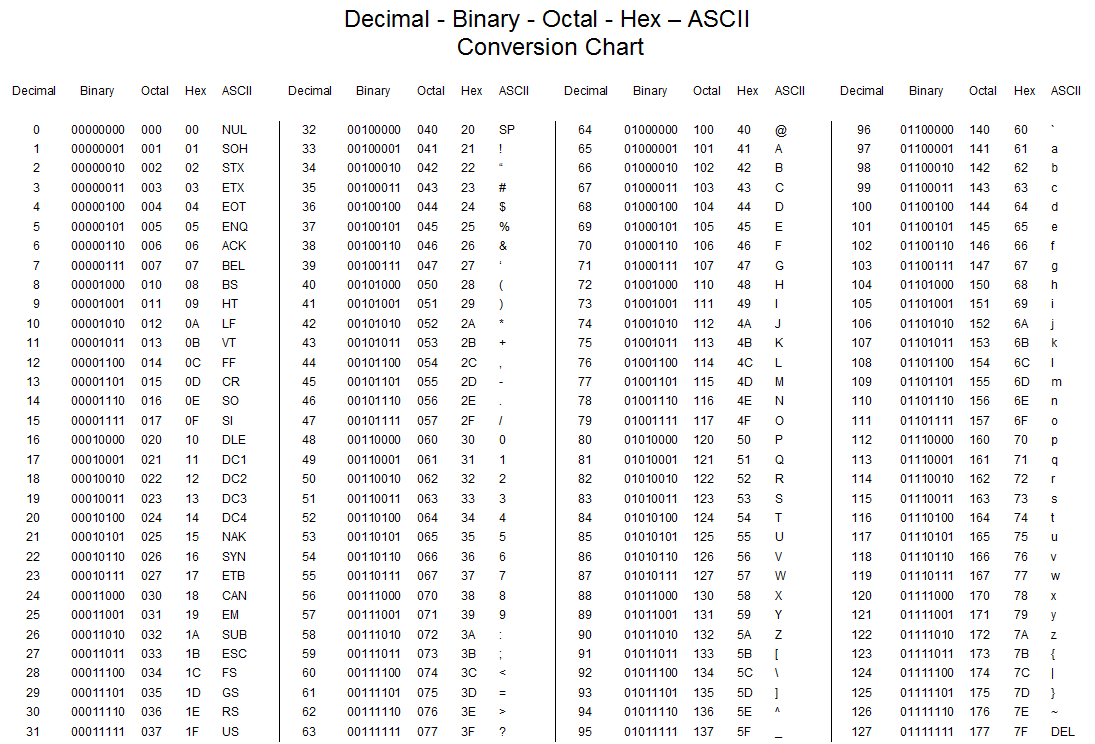

The decimal number systems¶

We are used to the decimal number system where we encounter numbers such 3, 42, and 89809.

Let’s look at the example

We can make the following observations about this decimal number:

The number consists of four symbols, each called a digit

Each digit can be one of ten possible symbols (either 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9).

The order of the digits matter. For example, the right-most one in 1314 represents the number of 10s whereas the left-most one represents the number of 1000s. A number system with ordering is called a positional number system.

We can rewrite the decimal number 1314 as

In general, we can write an digit decimal number as

Note that

10 is the number of symbols that can take on and is called the base of the decimal number system.

Let us now allow for an arbitrary base . Then we can write numbers as

where

is the base of the number.

For different values of , we get different number systems. Some examples are

: The decimal number system with possible symbols 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9

: The binary number system with possible symbols 0,1

: The hexadecimal number system with possible symbols 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, A, B, C, D, E, F

TODO The binary number system¶

A binary number

has base 2 and

is written only in terms of 0s and 1s.

An example of a binary number is

where the subscript 2 is here only added to make it explicit that is a binary number.

Note that

a ‘digit’ in a binary number is called a bit

a collection of 8 bits is called a byte with symbol B

a computer represents everything (numbers, colours, text, etc.) as binary numbers

Thus, the binary number has 8 bits and 1 byte (or 1 B)

Converting binary numbers to decimal numbers¶

To convert from a binary number to a decimal number, we simple use the expression

As an example, we get that 11012 converts to

Converting from decimal numbers to binary numbers is also possible, but is not covered here.

Adding binary numbers¶

You do it exactly as you learned in 2nd grade with decimal numbers. That is,

with 12 in carry

Using these three rules, we obtain $$ \begin{array}[t]{r} 0100\ 1001_2 \

\ 0111\ 1100_2 \ \hline 1100\ 0101_2 \end{array} $$

Example: Representing text using binary numbers¶

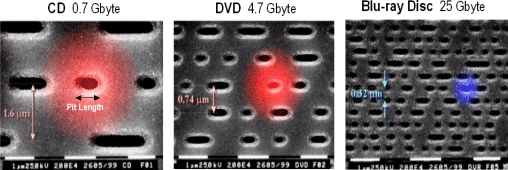

Example: Storing data on a disc¶

Information is stored by making tiny indentations known as pits on a disc.

A pit represents a 0

The opposite of a pit (called land) represents a 1

The binary data is stored along one long spiral on the disc.

CD: The spiral is 5.7 km long

DVD: The spiral is 12.3 km long

Blu-ray: The spiral is 28.4 km long

A laser is used for reading the binary data by following this spiral path.

Summary¶

A binary number

only contains 0s and 1s

consists of bits

A collection of eight bit is called a byte

Everything (numbers, text, images, video, audio, etc.) is stored and manipulated as binary numbers on a computer

The following slightly geeky joke is now funny ;)

There are 10 types of people in this world. Those who understand binary numbers and those who don’t!

Assignment¶

Bonus info:

With base , a binary number can be written as

G means billion (109), M means million (106), k means thousand (103), and B means byte (8 bit)

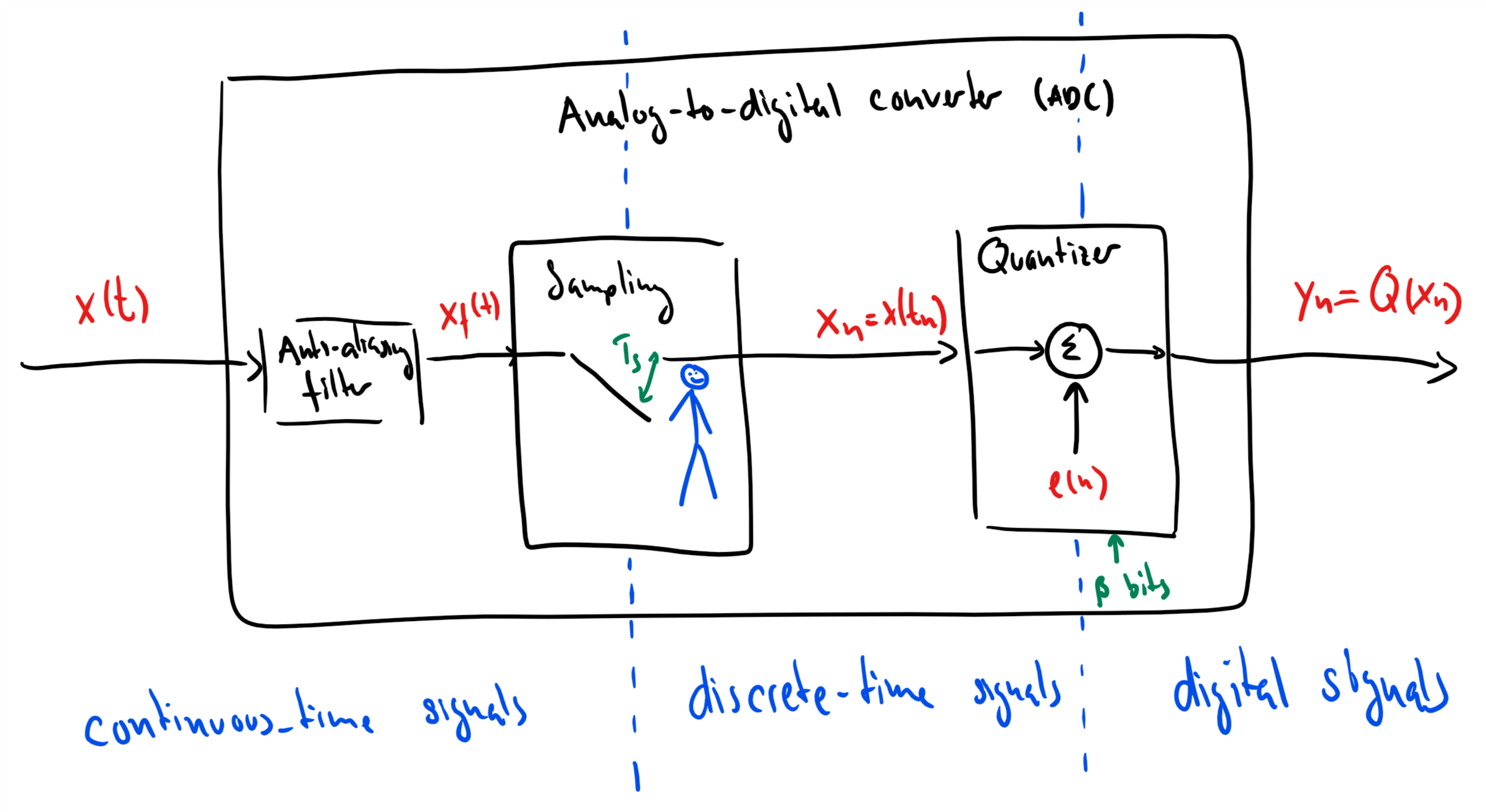

Quantisation¶

In the next 20 minutes, you will learn

What quantisation is and why it is necessary

How you will typically do it

What signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and dynamic range is

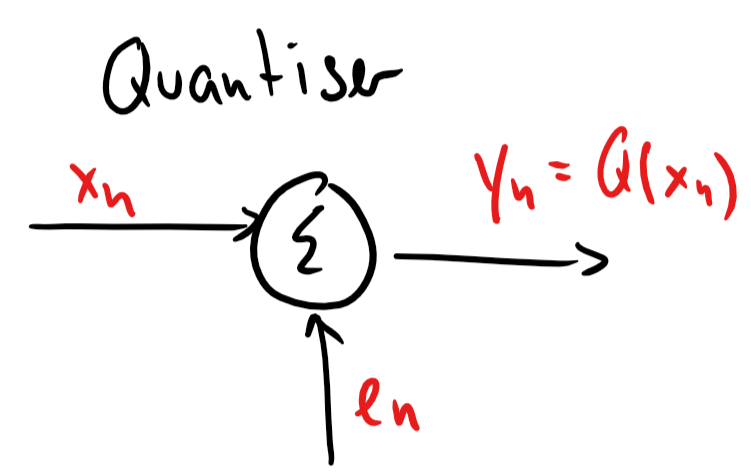

It requires an infinite amount of memory to store on a computer.

Therefore, we have to store an approximation to with only a finite number of digits. Let us call this approximation .

The approximation error can be written as

Example: Let contain only the first two digits of after the comma (i.e., ). Then

We say that we have rounded of (or quantized) to its nearest two-digits-after-the-comma representation.

The need for quantisation¶

Sampling converts a continuous-time signal into a discrete-time signal. That is, we go from an infinite number of time values to a finite number of time values.

However, we also have to do something about the signal value for every sampling time, so that we can store this number on the computer using a finite number of digits. This is called quantisation.

Uniform quantisation¶

Assume that we sample the signal value and that

the signal value is in the interval

we have bits available for storing this signal value. Note that we can represent different values with bits.

We now do the following.

Divide the interval into equally large cells, each of size

Round (or quantise) the signal value to the value at the nearest cell boundary, i.e.,

where and refer to the rounding and flooring operations, respectively.

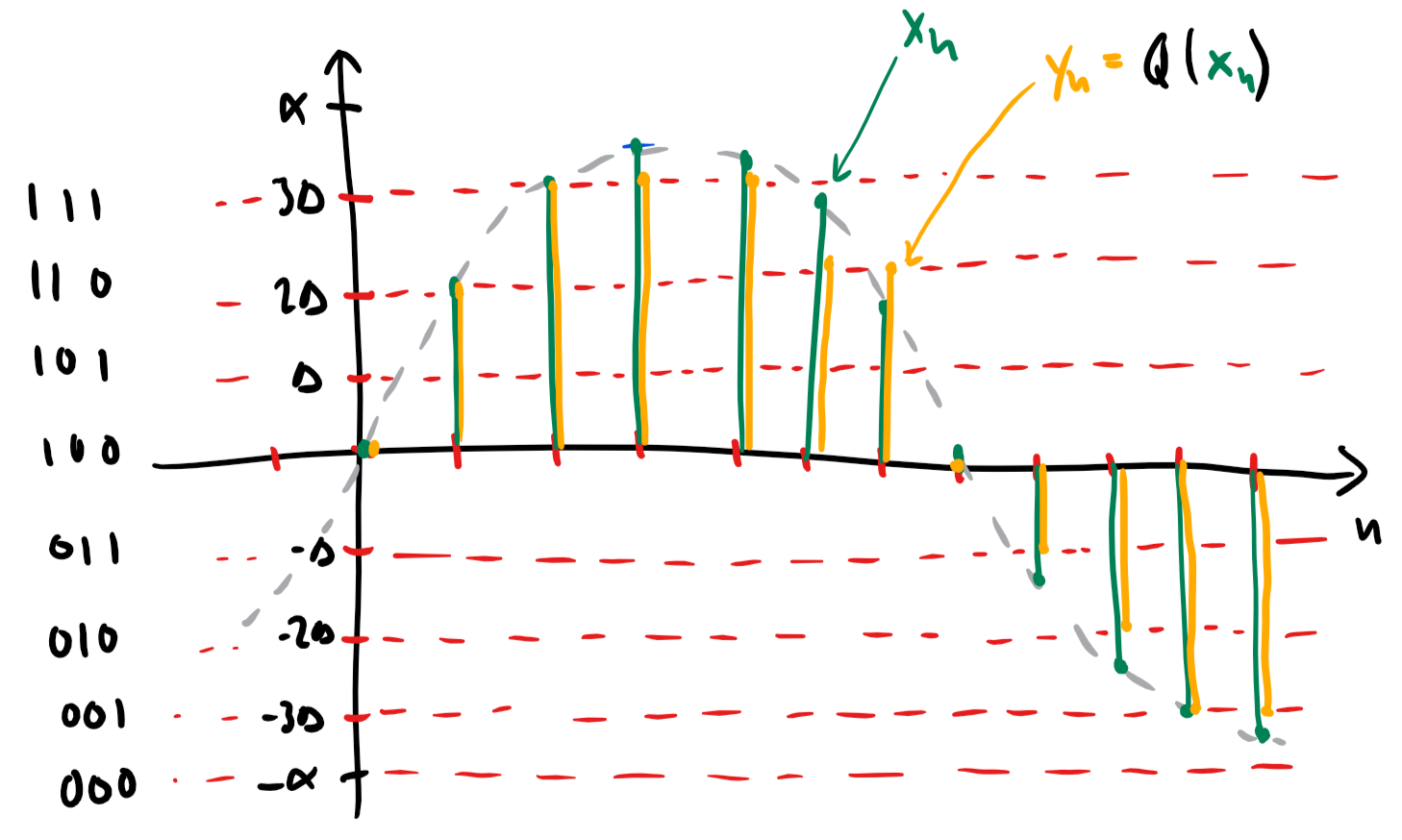

Example: 3 bit quantisation¶

In the figure below, the continuous-time signal (dashed gray) is first sampled (green) and then quantised (orange) using a three bit quantiser. The horisontal dashed red lines mark the quantisation levels. The final bit stream is

Quantisation error¶

The quantisation error is the difference between the signal value and its rounded value , i.e.,

We can rearrange this into

That is, we can think of quantisation as adding an error to the signal value .

A measure of quantisation quality is how big the average power of is compared to the average power of . The average power of, e.g., is defined as

If we define in a similar way, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is defined as

and it is measured in decibel (dB).

Now, assume that

the signal values take on values in equally often (a uniform distribution)

the quantisation errors take on values in equally often (a uniform distribution)

We then get

These results can be derived by computing the variance of a uniform distribution.

Finally, we get the SNR

Thus, for every additional bit, the SNR is improved by approximately 6 dB.

Dynamic range¶

The dynamic range is the ratio between the loudest and softest values we can represent using a bit quantiser.

Softest value: 1

Loudest value:

The dynamic range of a quantiser is thus

Thus, we get a dynamic range of 96 dB for a 16 bit quantiser (typical CD quality) and 144 dB for a 24 bit quantiser. Note that the dynamic range of the human ear is approximately 120 dB.

Summary¶

A quantiser rounds the signal values to a value on a grid.

All the points of the grid can be represented using bits which results in possible values.

Quantisation introduces noise into the digital signal. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) describes how powerful the signal is compared to this quantisation noise.

The SNR (and dynamic range) depends on the number of bits used as

Assignment¶

Think of ways for increasing the dynamic range without increasing the number of the bits. Hint = Could non-uniform quantisation work?